特工17中文下载官网|Agent17

v0.25.9,官朝向汉语获取

汉化版下载

📱 游戏详情

✂️ 玩法攻略

🎮 娱乐心意得标题

首先进展游戏剧情景后先输入各种特工17礼包码,切记端方面4个达成果礼包码单会选其唯一(在然而且选50刀...),输入礼包码当中型的方法法为打展背包,点手掌机,然后输入号码单行(礼包码广数个数人员应该都带有,我能把这次的礼包码起源地位于评论区),好多人物都有双条线,我都会讲(除完搞者基本没开发的)

首线:往习校>教室>先各个人物交谈下边>上面课>剧情里都是单一选项没什么估计说的( 接下去剧情中单一选项的我都不提了)>离开学校去后巷>Erica>随便选>回转家增上danu说话>摸头>左上快进际间>右边手机>每个个询问题问一遍>gold>让她给您买台电脑吧>设备>睡觉>瞧妈妈>去学校>luna>颜色看着选>请求另1个吻>教室上课>空教室>ophelia>我的电脑坏了,你能修好吗>去店铺街>礼品店>anriel>摸>站起来到>我的乌龟受伤了>随便选>点店铺街的胖子makoto>呼叫>amelia>对话完回家>danu房间找她>回本身己房间点计算机>快进时间>手机>休息(暂时不当作特工使命,后面别各个人物去做攻略,而因为50刀的礼包码里有特工的藏身处,所以便休息能各资源加10)>快进时间>danu房间>念办法开门>厨房>danu房间>开门>选第柒个>睡觉>妈妈能给我钱吗(赚钱的方法有很多,搞卫产,去医院卖蝌蚪,校长久办开室,找久师,礼品店整缘故娃娃,卖战利品给胖子待)>回自己房间>计算机>看邮件(这个爸爸真是好榜样式...)>窗户>gold房间找妈妈>敲门>问问danu第一次去海边的情况>去学校>快进时间>空教室>ophelia>去礼品店买望远镜和睡衣>回家回自己房间>计算机>去后巷>erica>回家找danu给她鲜睡衣

🌟 主必须特工17个体攻略

chloe:去咖啡店买arete jellify(顺便买arete糖浆)>傍晚她在的时候可以给她果冻>可爱式的>是性的>等chloe在的时候找她>不,我没有>隔日再找她>隔天再次找她出现新型的选项>玩个新游戏>去礼品店买个游戏转盘>回去找她>玩个轮盘游戏>脱掉一件>这里可以运用礼包码里的作弊作用>三次都选自己就行了(当然同时可以选她们俩,只要保证自己输就行了)>不跳舞>隔天再找chloe玩...的游戏>自己看着选吧(能增加好感上限)>多买几颗arete jellify,改天再找她>给她糖>玩....的游戏>把它放在你的嘴里>接下去自己看着选就行(完成增加好感上限)>改天再找她给她arete jellify(眼下应该好感是4心)>把chloe叫到达自己房间>快进时间>回自己房间找她>自己看着选吧(如果手头有5个arete jellify,可以往她买战利品)>隔天再找她叫回自己房间>这次激战需要提升她的唤醒度,直到可以进行下一步,各个选项都试一遍都能行的(不行的话就隔天再来)>完成后隔天再找她先给arete jellify,再选种个2心的游戏,然后游戏过程中有个5心的选项新增,点这个选项>成功后隔天再找她叫她去我们房间就特工17门户会解锁5心的和danu一起玩的选项,点这个(会提示需要和danu的相关系改善才可以,如果不行的话就去找danu提升对应的关系吧,束缚和糖基本是满的,好感只需要在danu一个人的时候给她糖以及者帮她做作业或者给chloe果冻,danu也会涨一点)>每个选项都选一遍>然后去超市买可乐>找danu给可乐>快进时间>去找danu>自己看着选吧>隔天再找chole>和danu、chloe做点务>自己看着选吧>隔天半夜去找danu各种选项试着提长她的唤醒度到超高(一次不行的话就第二天继续)>成功后自己回去睡觉发生剧情>隔天再找chloe叫到我们房间>玩游戏赚钱>这里存新档(开启chloe分支),目前没啥构成,chloe和danu的剧情就到这里了,等升级吧

gold:提升到2级按摩后晚上去房间找她>要我帮你按摩吗>隔天早上去她门口敲门>这里怕问题可以存个档再滴眼药水分(左右眼各一次就行)>不知道是danu剧情推进到一固程度再是再次在电脑里收到爸爸的邮件,某天睡醒会发生老妈进我们房间的剧情>问妈妈早上是否来过我们房间>先去自己电脑上学习隐形>半夜去她房间(需要加她属化先,在她洗碗时看她,看电视时看她,帮忙滴眼药水等都可以)>再敞开一点>目前等级不够,先离开>改天半夜再去找她>取下毯子>自己看着选>去电脑上看爸爸发来的新邮件(终于爸爸要给我们钱了)>接下去每天半夜都去找她,提升隐形经验然后去电脑上升级能力气>下次再来能看看相框(寻获取钥匙需要技能到4级)>只能不断重大复然后升级(4级的拼图还是有点难度的,看下面我发的图)>4级后半夜再去找她看看相框>取下钥匙(得到500)>目前剧情就到这里了,等待更新吧

这里特别提下,sakura和saphire是关联人物,saphire会出现两次分支,经过检验两次分支里容是一样的,只是选项略有不同,而要办妥sakura的总共计内容就必须在saphire出现后先移saphire的剧情,直到发现雏菊花,所以不可避免会有两次分支的采用,推荐一次选前者,另一次选后者,这样两个分支的剧情都会看一遍

sakura:中午给她拍照>找ophelia做rich simulated的换脸影片>早上上课在她旁边看电影>中午找她>早上上课继续>自己看着选吧>发生剧情选第一个>第二天早上会发生剧情>接受(不管接受还是拒绝最终都会远离sakura)>中午跟她对话>隔天早上会发生剧情出现特工17国语官网新人物saphire(其真不是新人物了,圣诞内容里的冰雪女王追到现实区域了)>这里先去看saphire的攻略,走她的剧情>saphire分支选完后中午找sakura>晚上请特工删掉视觉>早上去学校发现雏菊花>剧情后再次出现saphire分支(可存档)

aria:傍晚教室看到她>算了我会买>超市买可乐>傍晚再去找其>去咖啡店买咖啡>给她送去>第二天再买咖啡>把蝌蚪加入咖啡>去医院找purple买药>去医生办公室>第二天再去医院找医生>实验室>电视空的法使用>算好时间剪短电缆>这里自己看着选吧(之内后就可以来卖蝌蚪了)>晚上请特工操纵验血结果>白天去医院找医生(还是不给药)>晚上请特工想办法>隔天晚上去店铺街的书店>the freak>两种药都买两颗>傍晚带着两杯咖啡和药去找她>剧情后得到新照片>这是最好性的>如此精美>这里自己看着选吧>傍晚去找她>向她发送讯号>这里自己看着选(可以知道她热爱的礼物)>去咖啡店买耳环、两杯咖啡、晚上去书店买5颗肌肉减弱剂>隔天傍晚找她障碍和JAMES扳手腕>傍晚去找她挑战扳手腕>加5颗>给他们喝>这里每次都停在绿格上就可以,不行可以回滚重来>剧情后发起战斗,这里可以送礼,能加满好感度,然后自己看着选吧(特工17有两项会减好感度,起始后面可以增加好感度上限)...结束后得到战利品,aria的内容就到此为止了

sophia:买到延迟药后去医院找她>吃药>自己看着选吧(之后还能来但是没法继续深入了,作者还没开发)

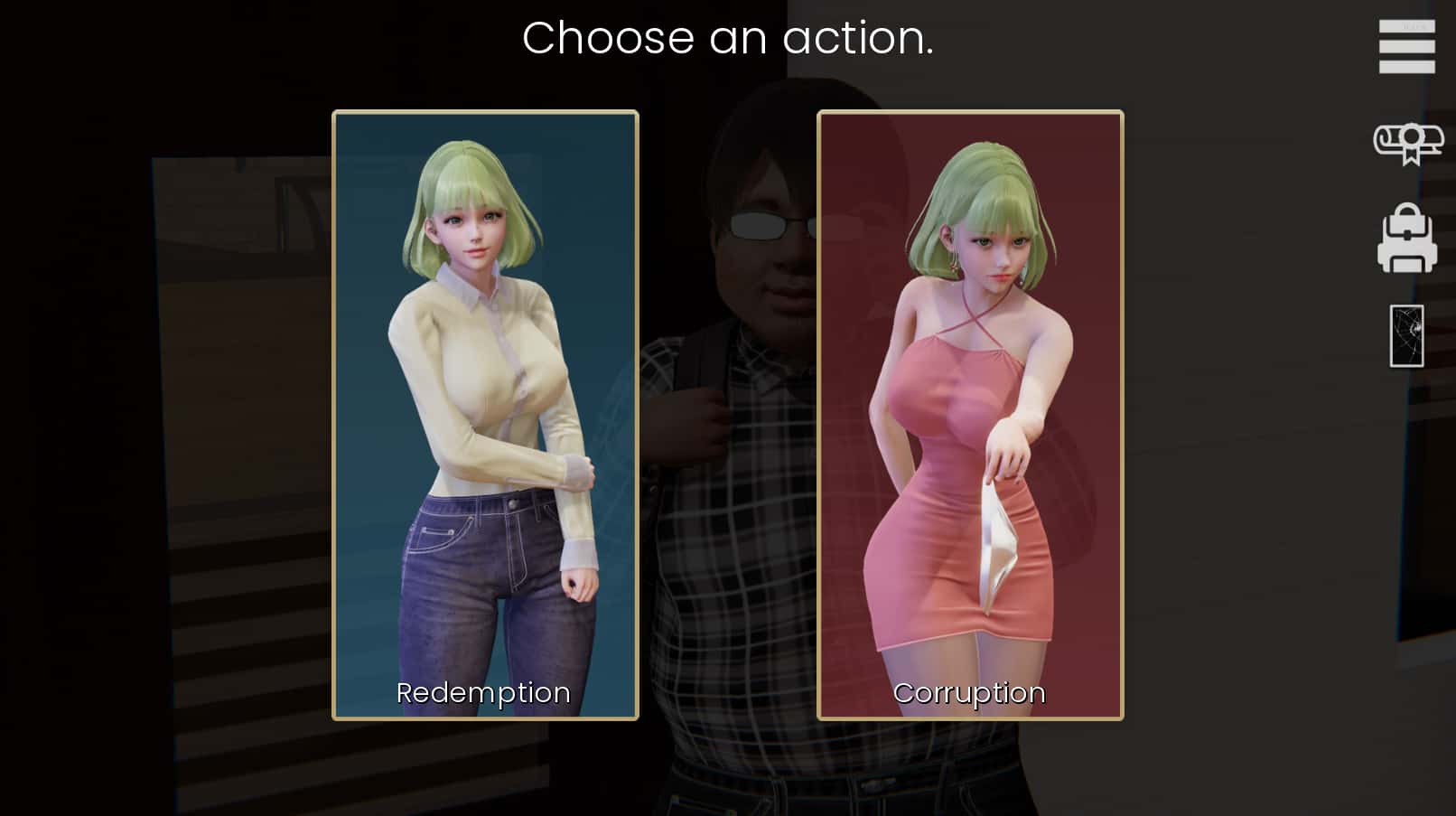

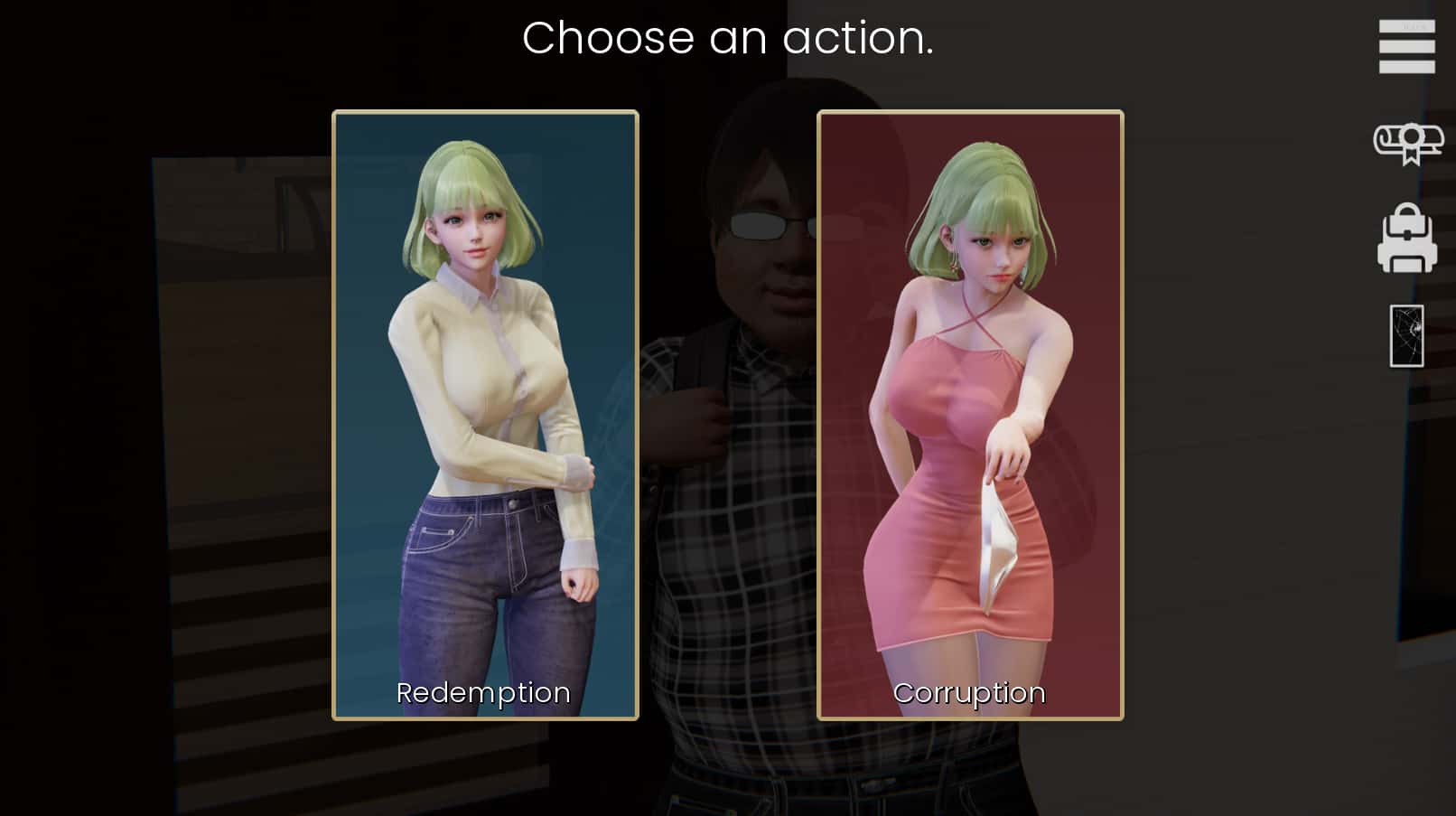

游戏截图

📩 汉化版下载

特工17中文下载官网|Agent17 已准备就绪,汉化版下载开始游玩。

下载游戏